AZBUKA in the news – the case for bilingual education

|

|

Opinion Language and grammar Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2021. All rights reserved.

Global Britain needs to improve its language learning

Better teaching methods that draw on the country’s diverse population could improve international understanding

School pupils take part in a language class. Demand for French and German is waning, while it is rising for Spanish © Red Snapper/Alamy

Andrew Jack AUGUST 17 2021

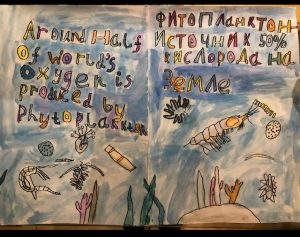

In a classroom this summer at Azbuka, a London bilingual primary school of which I am a governor, the children switched easily between English and Russian as they designed colourful posters in the two languages to help learn about coronavirus, climate change and mental health.

Not all have a Russian parent, including my son, who attended its Saturday complementary school some years ago. But their ability to absorb languages and cultures in a creative and engaging way is impressive and provides a lesson for Britain’s global ambitions.

Immersive learning that draws on the strengths of different cultural backgrounds remains an exception in England. Education is focused on the overly-academic study of foreign languages and too few people are convinced of their broader value.

A high proportion of people in London speak English as their second language, says Maria Gavrilova, Azbuka’s founder, yet they live a life of monolingualism. “There is a tragic unwillingness to explore successful methodologies and programmes for teaching foreign languages or maintaining first ones,” she says.

A recent survey by the British Council found that more than half of English primary schools stopped even rudimentary language teaching in the first lockdown last year and a fifth had still frozen their activities in early 2021. State schools in deprived areas were among those most affected. Nearly two-thirds of primary schools and two-fifths of state secondary schools reported no international activities last year, such as trips abroad or hosting a foreign language assistant, due to Covid restrictions.

Since the compulsory requirement to take a foreign language until the age of 16 was scrapped by the government nearly two decades ago, GCSE and A-level language qualifications have been in decline and a number of university modern language departments have closed.

Brexit risks depressing European language study still further, as fresh costs, new visa requirements and the axing of the Erasmus student exchange programme restrict the flows of assistants and teachers from former EU partner countries, and of students travelling to the EU.

Michael Kelly, emeritus professor of French at Southampton university, warns against complacency fuelled by the status of English as an international language. “We’re due for a fairly sharp awakening,” he says. “It’s already clear the EU is speaking more French and less English, and the Chinese increasingly expect others to speak their language.”

For Newcastle University’s René Koglbauer, chair of the board of trustees at the Association for Language Learning, an overhaul of language teaching is essential. He argues for a new national policy that puts greater emphasis on the value of languages and cultures, backed with more compelling ways of learning.

There are some positive signs. Rosanna Hume, a Teach First ambassador and head of Spanish at St Wilfrid’s Roman Catholic College in South Shields, says that although demand for French and German is waning, it is rising for Spanish, with students and their parents drawn to the language through music, TV shows and holidays. “Particularly in post-Brexit Britain, it’s more important than ever not just to know vocabulary and grammar but also to appreciate foreign cultures,” she says.

A pilot programme, The World of Languages, to be launched in several dozen primary and secondary schools this autumn, aims to inspire children by drawing on their own diverse heritage and exploring the links between different languages and cultures — including their role in the development of modern English.

“The only way out of the labyrinth is to celebrate the fact so many of our kids are bilingual. Why are we not doing more to build on that?” says John Claughton, one of the developers and former head of King Edward’s School, Birmingham. “Make them the poster boys and girls of languages. There is a future for celebrating multilingualism.”

Not all families or communities are multilingual, of course, and bilingualism is not easy to maintain for those that are. But even monoglot English speakers would benefit from greater appreciation of the foreign influences on their own tongue and ways to engage with other cultures.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2021. All rights reserved.